The Regions of Bordeaux

Posted 2 March 2020

by Jamie Ashcroft

France is known as a powerhouse for expensive and high-quality wines, with Bordeaux at the heart of its reputation. But while many know where the Bordeaux area is in the country, not many know of its various sub-regions, appellations and communes or the little differences between them which can create very different wines.

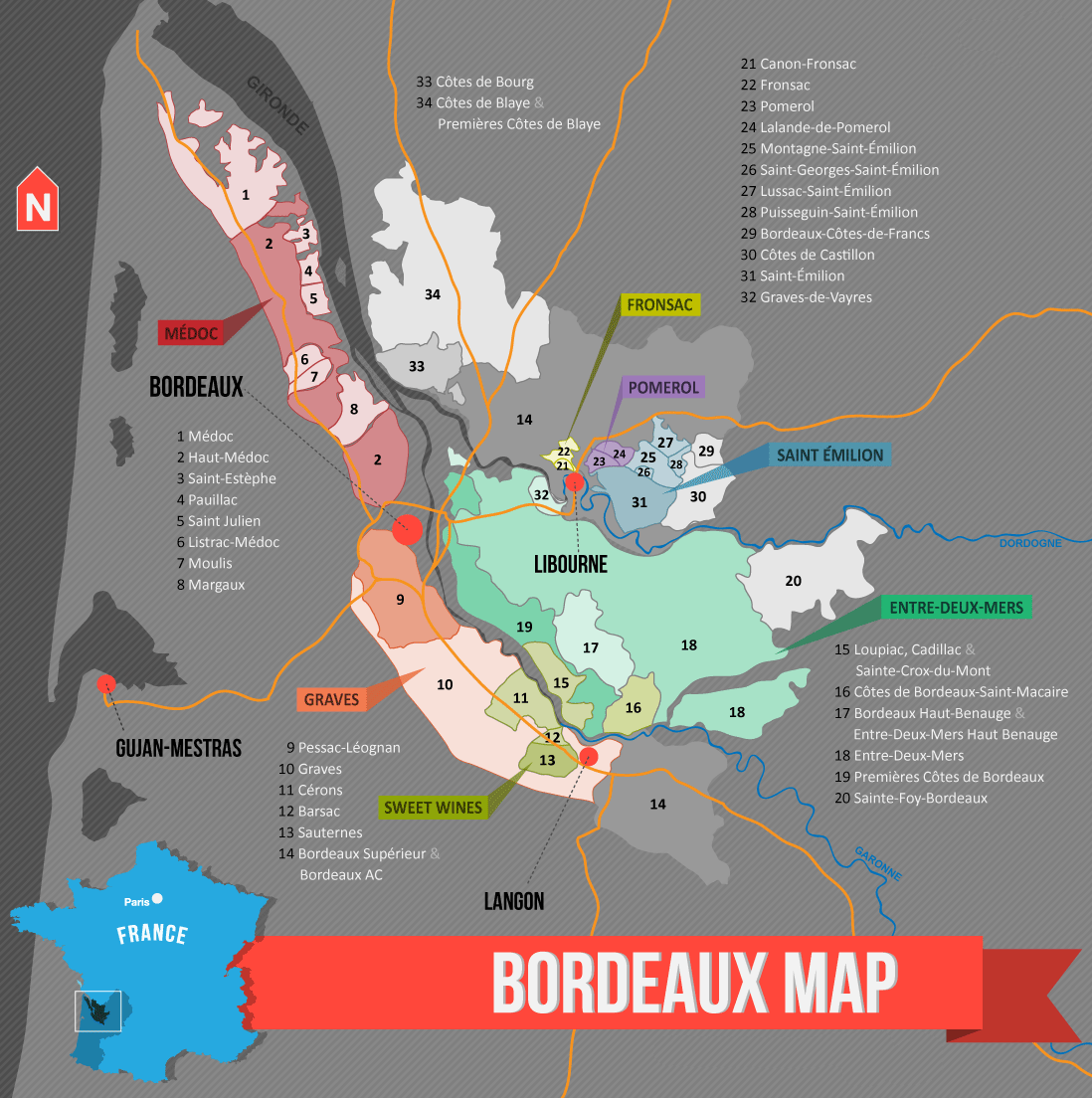

Bordeaux is a wine region in Western France, bordering the Atlantic Ocean where the Gironde Estuary moves inland. The Gironde (before splitting into the Garonne and Dordogne rivers further inland) naturally divides the region into its Left Bank and Right Bank. Further inland and upstream, between the rivers Garonne and Dordogne, lies another region: Entre-Deux-Mers (literally Between Two Seas), which produces several less-famous sweet wines among others. All of these regions contain subregions known as appellations (AOCs), governed by their own laws on which grapes are allowed to be grown, what style of wine can be produced, winemaking, pruning and picking techniques that can be used, density of vines and wine alcohol levels, making each unique – and across Bordeaux there are around 50 separate appellations.

A detailed map of the main AOCs of Bordeaux, courtesy of Wine Folly

While each AOC will have its own laws for wine production, all must create their blend using grape varieties permitted in Bordeaux: Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Malbec and Petit Verdot for red wines and Sauvignon blanc, Sémillon and Muscadelle if making white. This is what the term ‘Bordeaux Blend’ means. A more general rule for differentiating Bordeaux wines is that Left Bank wines tend to be Cabernet Sauvignon-based while Right Bank are more Merlot-based, resulting in different characteristics in each.

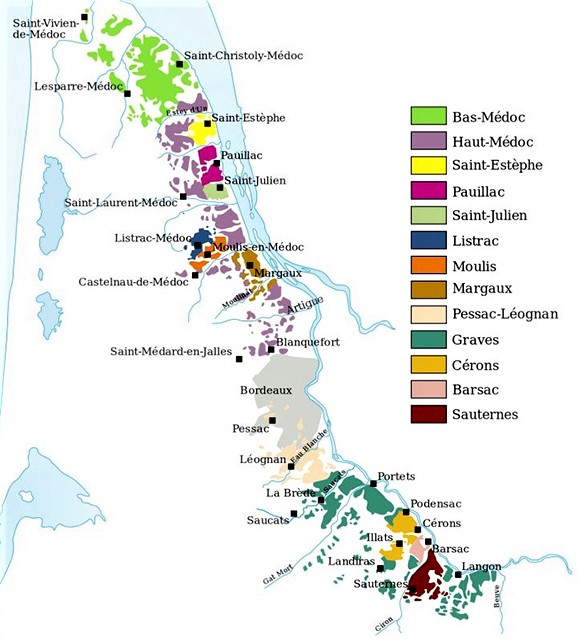

The Left Bank contains a number of famous regions; Bas-Médoc (now labelled simply as Médoc) in the north with clay-based soils which produces wines closer to the Right Bank style, Haut-Médoc further south which contains AOCs such as Margaux, St-Julien, Pauillac and St-Estèphe, and Graves on the edge of the Garonne river further south, containing Pessac-Léognan, Sauternes and Barsac.

AOCs and areas of the Left Bank of Bordeaux

St-Estèphe, the northernmost commune of Haut-Médoc, with its heavy clay-composite soils, has more of a planting of Merlot grapes than any other Haut-Médoc region. This region produces wines generally less perfumed and more acidic than other Bordeaux wines, and its clay soil gives an advantage in hot, dry summers as it is slow to drain.

Pauillac lies south of St-Estèphe and contains three of the five first growth estates in Bordeaux, the Châteaux Lafite-Rothschild, Latour and Mouton Rothschild, making it infamous for high-quality and expensive wines.

St-Julien has the smallest wine production of the four famous Médoc regions, but also the highest proportion of classified estates in Bordeaux. Nearly 80% of the region’s production is from classed growths.

Margaux, the most southerly of the four big Haut-Médoc appellations, contains not only a first growth estate in Château Margaux but also 21 other classified growths – giving the area more than any other AOC.

Pessac-Léognan, found in the northern part of the Graves south of the Médoc, is home to the only first growth estate outside of the Médoc: Château Haut-Brion.

Sauternes and Barsac lie further south in Graves and are known for their sweet white dessert wines like the famous Château d’Yquem. The sweetness of these wines is due to Botrytis cinerea (noble rot), a fungus which desiccates grapes to concentrate the sugar inside, leaving residual sugar in the wine produced from them. These wines can be very expensive as their production is so difficult; the desiccation means yields five or six times lower than the rest of Bordeaux, and harvest is usually performed grape-by-grape, pickers wandering up and down vineyards over the course of three months to individually select grapes at their peak. This, along with the fermentation of the wine in small oak barrels, makes production a long and expensive process.

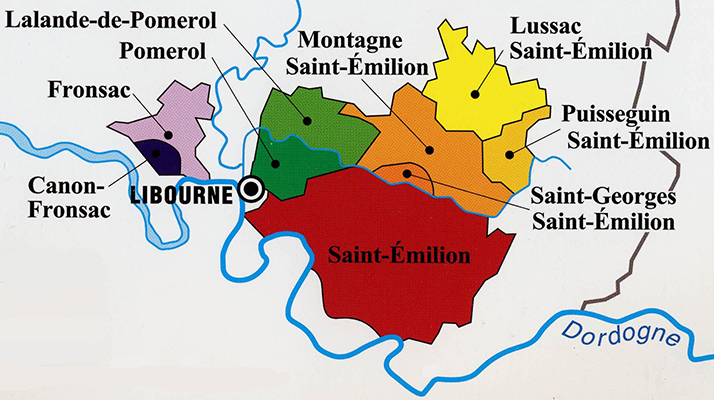

The Right Bank is largely made up of an area called the Libournais, containing the famous Pomerol and St-Émilion, but also contains the regions of Côtes de Bourg and Côtes de Blaye. Generally however, the term ‘Right Bank’ will refer to the AOCs of Pomerol and St-Émilion.

The Libournais, containing St-Émilion, Fronsac and Pomerol

Pomerol, first cultivated by Romans during their occupation, produces wines considered generally as the gentlest and least tannic or acidic of Bordeaux. The blend specific to this AOC, while using Merlot as their leading grape, uses Cabernet Franc second rather than Cabernet Sauvignon, giving Pomerol wines their deep, dark colour. Because of the lower levels of tannins and acidity in these wines, Pomerols are typically drunk much younger than other Bordeaux wines and will age faster.

St-Émilion, sharing its western border with Pomerol, also uses Merlot and Cabernet Franc as the leads for their blend. While wines from this AOC share Pomerol’s ability to be drunk early, they can mature slightly longer in general and in the case of a good vintage can have good potential for ageing (if stored correctly).

Vines in the Blaye region of Bordeaux

North of the Libournais, the Côtes de Bourg and Blaye form one of the oldest wine regions in Bordeaux. Merlot is here followed by Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Malbec in blends, although certain areas have Sauvignon blanc vines for sparkling wines or Ugni blanc for cognac (north of Bordeaux).

Bordeaux is a large and fascinating area, producing some incredible wines from all its regions. This overview has only scratched the surface, but now you know the most influential regions and some of the key differences between them. Each region has its own quirks and personality, which translates to their own unique styles of wine – and if you know which area a wine bottle comes from, now you should have more of an idea what you might find inside!